Luxury hotels may be facing a new divide. As ultrawealthy guests snap up top-tier suites and villas, entry-level luxury rooms may sit empty, signaling a growing bifurcation within the luxury market.

“Around the end of 2024, we saw deluxe rooms were becoming a lot harder to sell than the suites,” said Jack Ezon, founder and managing partner of luxury travel advisory Embark Beyond.

In the company’s Q4 2025 Travel Trends Report, he characterized this shift as a tale of two markets.

“Luxury travel has become distinctively bifurcated — the ultrawealthy and the, well, the poor rich,” he wrote. “Inflation continues to squeeze the aspirational luxury traveler. Suites are going for higher rates than ever and quickly sell out, while base-rate deluxe rooms or opening categories remain barren.”

This luxury divergence mirrors what economists have been calling a broader K-shaped economy, in which high earners surge ahead while lower earners lag behind. A widely cited report from Moody’s in 2025 found that the top 10% of earners accounted for nearly half of all U.S. consumer spending, a historic high.

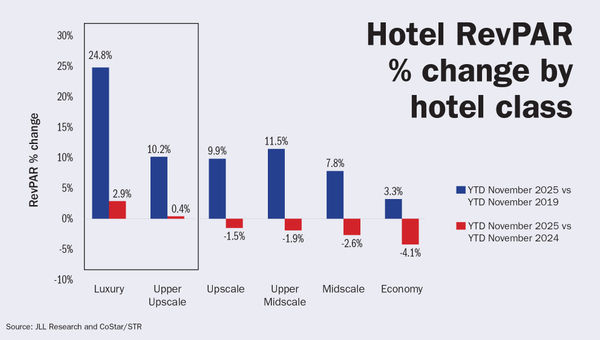

It’s a pattern that’s also playing out across the hotel industry as a whole. Year-over-year RevPAR performance data through November from JLL Research and STR/CoStar shows luxury hotels gained 2.9%, while upper upscale managed just 0.4% growth, upscale dropped 1.5%, upper midscale dropped 1.9%, midscale dropped 2.6% and economy properties dropped 4.1%.

A separate K shape for luxury

Now, however, it appears that a “K” is emerging within the luxury segment itself.

This widening gap within luxury reflects larger demographic shifts, said Carine Bonnejean, global head of hotels at U.K.-based advisory firm Christie & Co.

“There is a clear widening of the luxury segment,” Bonnejean said. “The number of millionaires is increasing rapidly, and therefore the luxury segment is segmenting even further to adjust to all types of clients, from ‘entry’ younger wealthy people to ultraluxury HNWI [high-net-worth individuals] looking for the most exclusive ultra-personalized experience.”

Hotels are responding by reconfiguring their product mix.

Jon Makhmaltchi, founder and CEO of luxury travel marketing company J.Mak Hospitality, said properties are remodeling to make smaller rooms larger and adding villa inventory to meet demand for premium accommodations.

“Hotels are actually taking rooms out of inventory and converting them into suites,” said Makhmaltchi, citing examples like the AlmaLusa Baixa/Chiado in Lisbon, which recently transformed some existing room product into a two-bedroom accommodation, and the Saint James Paris, which purchased an adjacent property to expand with four luxury apartments.

“Their regular rooms were sitting empty, but their high-end inventory was booked,” Makhmaltchi said.

He added that he’s seen some luxury properties offer advisors enhanced commissions of 12% to 15% on entry-level inventory to help drive bookings.

Premium luxury product, however, requires no such incentives, with ultrawealthy travelers adamant about securing top-tier accommodations.

“Because if that presidential suite isn’t available, they’re not going to level down,” said Makhmaltchi. “They’re either changing their dates to get it, or they’re finding an alternative property.”

Adding to the divide is something Ezon acknowledged in Embark’s Q4 report: “Many hotels are sticking to higher rate and lower occupancy.”

“They’re keeping with a strategy that says I’d rather have my hotel at 65% occupancy at a higher rate instead of 100%, and hire less staff because the cost of operations is so expensive,” he said.

Dan Peek

Dan Peek, Americas president for JLL’s Hotels & Hospitality Group, echoed that sentiment, saying that for hotels, the post-pandemic recovery has largely been rate-driven, with luxury operators testing pricing limits.

“They may well have pushed the envelope so far that that aspirational traveler may get priced out,” said Peek, though he characterized any evidence of this as “anecdotal more than actual data.”

Is the current path sustainable?

Peek emphasized, however, that luxury fundamentals remain strong, pointing to hotel supply-and-demand dynamics that favor continued growth.

“We’ve increased the supply of luxury travelers,” he said. “We really have not increased the supply of luxury assets for them to choose from. And as long as they’re confident and they feel liquid, they will continue to travel.”

Ezon took a different stance, expressing doubts about the current model.

“I’m not sure how sustainable” it is, he said. He added that in his 25-year career, he’s never seen luxury hotel rates accelerate as dramatically as they have in the past four years, potentially pricing out entry-level luxury consumers.

“You no longer have this new pipeline of people if you alienate them,” he said. “Ownership, I think, needs to be humble and take a more strategic approach.”

Ezon emphasized that while the luxury market appears robust now, it remains heavily dependent on continued economic strength.

“Right now, it’s a thriving market,” he said. “As long as the stock market is strong, financial markets are strong, it will do fine. But [if] markets start to compromise, things will start to slow down, because then even the richest people spend money differently.”

Not everyone sees the trend as a clear bifurcation, however. Henley Vazquez, co-founder of travel advisor network Fora, said the shift is more nuanced, with affluent travelers increasingly mixing and matching experiences and price points, perhaps staying at lifestyle hotels in cities while splurging on ultraluxury resorts for family vacations.

“Luxury travel is healthiest when it serves a spectrum of travelers, not just the very top,” added Vazquez. “Advisors help maintain that balance: Ensuring luxury remains aspirational and accessible rather than exclusionary, and helping travelers navigate an increasingly complex landscape with confidence.”